- 7-1 Creating a Budget

- 7-2 Funds from the Municipal Budget

- 7-3 Town Conservation Funds

- 7-4 Grant Programs

- 7-5 Other Funding Sources

- APPENDIX A: SAMPLE RULES FOR MUNICIPAL CONSERVATION COMMISSIONS IN VERMONT

The two most limiting resources for conservation commissions are usually time and money. This chapter covers aspects of a conservation commission’s finances, including sections on budgeting, fundraising, and starting a local conservation fund. By investing time in understanding how to pay for conservation work, you can help advance your conservation commission’s goals, and become a higher functioning part of municipal government, as well as a valuable conservation partner.

7-1 Creating a Budget

Creating a budget for your conservation commission is an important step to ensure that you have the necessary resources to complete your workplan. The size and complexity of the budget will vary by town, but at minimum should lay out any expected sources of revenue and any operating expenses.

Conservation commissions typically have four sources of revenues:

- Municipal funding;

- Funds or grants from public sources such as state or federal programs;

- Funds or grants from private sources such as foundations or businesses;

- Revenues from various fundraising events.

Operating expenses for conservation commissions can include costs such as;

- Membership dues to the Association of Vermont Conservation Commissions;

- Technology and hardware (computers, external hard drives, game cameras);

- Software (GIS, Microsoft Office);

- Travel reimbursement;

- Training, meeting, and conference costs;

- Stewardship (e.g., lumber, tools, contractor labor);

- Water sampling equipment;

- Printing, photocopying, and postage costs (maps, flyers, newsletters, etc.);

- Educational program costs (Walks and Talks series, etc.).

Commissions should draft annual budgets for those expenses. It also is good practice because commissions will need to become proficient at drafting budgets for larger projects requiring grant applications. For any budget request, a commission should state why the funds are needed and what they will be used for. Descriptions of past successes, future partnerships, and benefits to the community all increase the likelihood of acquiring funds.

7-2 Funds from the Municipal Budget

For conservation commissions, most operating funds, that is, the money needed to run day-to-day operations, are obtained through the municipal budget. The enabling legislation states that a conservation commission may “receive appropriations for operating expenses including clerical help by appropriation through the budget of the legislative body.”

Most conservation commissions do receive annual operating funds from their municipal budgets. Some conservation commissions work for years (especially the first year or two) with no operating funds from the municipality. But typically, these commissions are given access to parts of other budgets within town government, such as the planning commission’s or selectboard’s funds. The key to any type of fundraising is to ask for the money that is needed! Some commissions receive no town funds because they have not asked for it.

Conservation commissions need to learn the budget cycle in their municipalities as well as the process for requesting funds. They need to find out who is responsible for preparing the municipal budget, when budget requests should be submitted, and what information or supporting data should be included in the request.

Generally, the conservation commission submits an itemized estimate of budget needs for the coming year to the selectboard or a municipal employee. The selectboard reviews all funding requests and compiles a draft town budget, which is presented at a public hearing. After the hearing, the final budget is prepared and is included in the Town Report for voting at Town Meeting. After a budget for the conservation commission is approved, the treasurer of the commission must keep accurate records of expenses (e.g., bill and/or receipts) that are submitted to the municipality for payment or reimbursement.

A conservation commission can also submit a request for a town appropriation for a specific project, such as a specific capital expenditure to purchase a parcel of land. This could appear as a separate article on the town warning or could be a line item in the municipal budget. However, a better approach may be to establish a local conservation fund, as described in the next section.

7-3 Town Conservation Funds

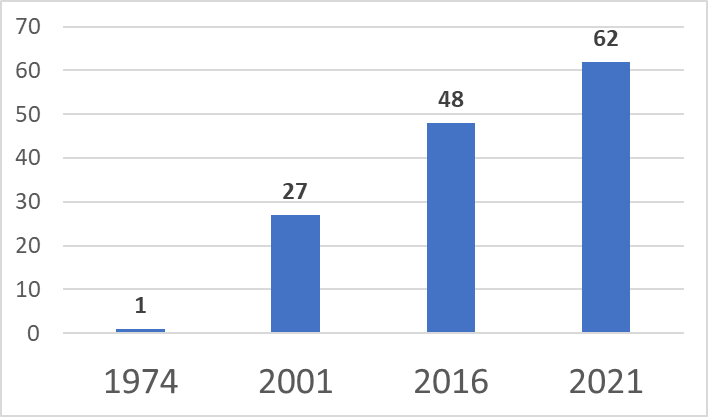

A conservation fund is a dedicated fund set up by a municipality for conserving lands and waters for agriculture, forestry, wildlife habitat, scenic attributes, recreational use, or natural areas. The real estate can be bought outright via a fee acquisition or protected by the purchase of development rights. Since the establishment of the first local conservation fund in 1974 by the Town of Norwich, at least 62 towns have established a conservation fund, representing approximately a quarter of all Vermont towns.

Local conservation funds have been highly successful throughout Vermont. Towns with such funds have preserved many important parcels of important conservation lands. For example, East Montpelier has used its local fund to protect over 3,000 acres in town, representing 72% of the conserved acreage within town. In Williston, the town’s Environmental Reserve Fund has helped conserve 2,252 acres, resulting in a $2.4 million investment for a total value of $5.2 million over the life of the fund. A local conservation fund shows a town’s collective commitment to protect what the citizens value about their town. This funding program takes a strong community belief and puts a financial commitment behind the words of responsibility and stewardship. Such a fund is a long-term public investment in land conservation.

Benefits of a local conservation Fund

There are many advantages to having a local Conservation Fund, including:

- “Leveraging” or tapping into matching funds;

- Advancing town goals;

- Enables town to engage and focus on its local conservation priorities, versus those of other conservation organizations;

- Speeding action and providing flexibility to act on fast-moving projects;

The following sections will explore these benefits in greater detail.

“Leveraging” Or Tapping Into Matching Funds

Most land conservation projects involve multiple funding partners, and a local conservation fund is often a critical piece in this equation. Beyond its direct dollar value, the fund will often attract to the project additional financial partners who view the fund as proof of the townspeople’s commitment to conservation. Thus, every dollar invested in the fund can leverage additional dollars from other funding sources. Leveraged funds are a financial commitment towards the cost of a project from a source beyond the granting organization. Most grant programs require a certain percentage of matching funds from applicants. There is strong competition for land conservation funds from state, federal, or private sources. Projects that include local public dollars, such as from a local conservation fund, are often viewed more favorably because these local dollars show the townspeople’s commitment to being a paying partner in the project. From the funder’s perspective, this also signals that you have done the organizing work ahead of time for the project to succeed.

Richmond Conservation Reserve Fund: After an earlier attempt narrowly failed to win voter approval, in late 2004 the Richmond Conservation Commission tried again. In a single day at a holiday fair, volunteers gathered enough signatures on a petition that compelled the Selectboard to put an article before voters on Town Meeting Day 2005 calling for the establishment of a Conservation Reserve Fund. The commission then worked with the Selectboard to write the article, setting a funding level of one cent on the tax rate for five years. Read More

Often, a modest sum from a local Conservation Fund can access many times that amount through various grants and programs. For example, from 2000 to 2018, the Huntington Conservation Fund spent $96,000 of town dollars, leveraging another $576,750 of funds from other sources. Put another way, each dollar Huntington contributed through its fund generated $6 from other sources. Moreover, this local match is usually much smaller than the amount received from other sources. For the purchase of its town forest in 2021, Montpelier received $258,000 from the USFS Community Forest Program to expand Hubbard Park. The Town Conservation Fund contributed $20,000 and an additional $35,000 came from private fundraising. Partners included the Montpelier Conservation Commission, Montpelier Parks Commission, & the Trust for Public Land.

As in the case with Montpelier, leveraging is also about working together with partners. Towns with a particular conservation project idea can often find partners, such as land trusts, state agencies, or other organizations that can provide expertise and assistance. Many of these groups have specialized niches. The Upper Valley Land Trust works within a specific region; The Vermont River Conservancy, on the other hand, focuses on conserving Vermont’s river corridors and public swimming holes.

Where does the conservation commission fit into all this? If Conservation Fund dollars are on the table in a multi-partner conservation project, the conservation commission should play a leading role in rallying local support for the project. While outside partners may be able to provide expertise on land conservation, they cannot compete with locals when it comes to spreading the word and building relationships in town. For example, if the town is hosting a joint event with a partner organization, the conservation commission can spearhead efforts to spread the word and boost attendance at the event.

Orange County Headwaters Project (OCHP): The Orange County Headwaters project began to emerge in 2002 in the towns of Corinth and Washington, VT. The project stemmed from a community interest in maintaining the character of the area in the face of increasing development of these largely forested and agricultural towns due to the short commuting distance to Barre/Montpelier and the Upper Valley area of VT and NH. As towns surrounding the area became increasingly more fragmented by development, the landowners of Corinth and Washington decided that they needed to do something to stabilize the land uses in order to act as a way to mitigate their towns’ lack of zoning. Read More

Advancing Town Goals

Another benefit of a local conservation fund is that the funded projects may help the town achieve local community goals described in its town plan or other town reports. For example, many local funds state that one of the fund’s goals is to preserve the town’s rural character and its working agricultural and forested landscape—very similar language to what is found in most town plans. For example, the first of several goals in the East Montpelier Conservation Fund is to “Maintain the rural, working, land-based character of East Montpelier…” Other town plan goals that can benefit from a local conservation fund program include protection of wildlife habitat, water resources, and recreational opportunities. In addition, a local conservation fund represents a non-regulatory approach to land use planning; it is a local mechanism that includes the participation of willing landowners.

Conserving Local Priorities

Local sources of funds are also critical to land conservation efforts because regional and statewide organizations cannot undertake all of the potential projects. These groups have limited funds and resources and thus must prioritize their work, often across large geographic regions. As such, a particular parcel of land may be very important for the town’s conservation goals, but a statewide organization may not be interested in the project because it is not of regional or statewide significance, or their funding priorities might not match a town’s priorities for a particular project. In such cases, a local conservation fund may be the difference between a successful land conservation project versus the land being developed. Moreover, regional and statewide groups are not as familiar with individual towns and their needs.

Speeding Action

Another benefit of having a local conservation fund is the ability to move quickly on a potential project. The chance to conserve an important parcel of land can arise suddenly. With a local fund in place, town officials can move the proposal through the application and review process quickly, potentially before the opportunity is lost or before costs rise. This is particularly true in towns with policies that do not require a town-wide vote to expend the conservation funds. For example, the Brattleboro Agricultural Land Protection Revolving Loan Fund may be used to provide short-term financing when conventional financing cannot be arranged quickly enough. Moreover, with such a local program in place, a town can seize the opportunity to move from a reactive mode to a proactive mode in land conservation. Instead of waiting for certain landowners to come forward or for a certain parcel to be put up for sale, a town can inventory its natural resources and prioritize key areas or parcels for conservation projects. Then, landowners can be approached to see if they are interested in participating in this program.

Legal Mechanisms for Establishing Conservation Funds

The authority to establish a town Conservation Fund appears in multiple sections of Vermont Statute. Most Conservation Funds are types of reserve funds that are under related statute (24 VSA §2804) are established by a vote of the municipality and placed under the control of the legislative body (i.e., Selectboard, City Council). This statute allows for towns to set up reserve funds for whatever funds they deem necessary. The municipality votes to create the fund at its annual meeting or at a special meeting duly warned. Williston, for example, is one town that established its fund this way.

Conservation Funds, however, can also be established under the powers and duties of conservation commission (under 24 VSA Chapter 118 §4505(5)), through their ability to “receive money, grants or private gifts from any source” for conservation purposes. Moreover, the ability to raise funds is a logical extension of the authority of conservation commissions to recommend that the municipality purchase key properties (24 VSA 2405[3]). Thus, the enabling legislation for a conservation commission allows it to set up a conservation fund without a vote of the citizens. Thetford is one town that set up a conservation fund this way. In Sharon, the conservation commission asked the town selectboard to sanction the establishment of a fund. Another Vermont Statute addresses local land conservation: 10 V.S.A. Chapter 155 Acquisition of Land by Public Agencies. This chapter encourages the maintenance of Vermont’s agricultural, forest, scenic, and recreational lands and discusses the power of municipalities to acquire real property or rights or interests therein by purchase, donation, transfer, or other methods.

A municipality can use the authority under Section 2804 to create a reserve fund even if it does not have a conservation commission. For example, the Town of Warren created a Reserve Fund before it had a conservation commission. In general, though, town Conservation Funds are better positioned with oversight by an organized body, such as a conservation commission, or even a special entity whose purpose is to oversee and administer the Conservation Fund.

Laying the Groundwork & Building Support

The initiative to form a local conservation fund can come from any citizen of the town. Most often, conservation commissions have been the leaders on this issue. Others who can promote the formation are the selectboard, the planning commission, or the local land trust. The Charlotte Land Trust initiated the formation of the conservation fund in its town. In Bolton, one citizen stood up at March Town Meeting and successfully proposed the establishment of that town’s fund during discussion of the municipal budget. However, in many towns, successfully forming a Conservation Fund will require careful planning and strategizing.

Cornwall Conservation Fund Appropriation Approved by 86% of Voters: Cornwall has had a Conservation Fund since 2016, proposed and defined by the Conservation Commission and Cornwall Planning Commission and approved by the Select Board. However, up until March 2021, there had been no approved appropriation of money into it. At the March 2020 Cornwall Town Meeting, voters approved the creation of a Conservation Fund Planning Group to study how towns in Vermont fund their conservation activities. Read More

Distributing a survey to community members is another way to gather thoughts on the topic, gauge willingness to pay, and help identify priorities for what the fund should be used for. You may need to take on a campaign of persuasion to convince people why this is a good use of their tax dollars. Write letters to the editor of your local newspaper; post on Front Porch Forum; Host a series of educational walks and talks on conserved lands. Other options include holding a public meeting before the voting day, and garnering support from other town officers or community groups. Town residents speaking in favor of the article at town meeting is an effective way to educate voters. One town handed out an information sheet at town meeting. Networking throughout town and sharing ideas with nearby towns that have conservation funds are also beneficial strategies. For example, the Town of Charlotte undertook a series of efforts to promote formation of its fund: It commissioned an in-depth study that helped with educational and outreach efforts; results from the study were widely disseminated, through letters sent to all households, and at a public hearing to present the findings of the study. Letters and articles debating the pros and cons of the local fund were published in The Charlotte News.

Weeks Forest Carriage Trail: For many years the Guilford Conservation Commission has envisioned a network of public trails in our town with the goal of building appreciation for our natural resources. Much of our work in recent years laid the groundwork for this vision. We have organized monthly walks to explore our natural resource and historic landmarks. We created a guide and map of Guilford’s recreational resources for our town’s 250th anniversary. We researched and documented several Guilford “ancient” and Class IV roads for reclassification to Legal Trails in 2015. We worked with our Planning Commission in 2015 to write the Natural Resources section of our Town Plan, which included the goals of developing public trails and a Trails Committee in our town. Read More

Promoters of a conservation fund should consider the timing of their proposal. For example, is their community facing a large tax increase this year? If you are getting the signal that there is not enough support for a Conservation Fund at the moment, use that awareness to refocus your efforts on building the necessary support before you bring it up for a vote at Town Meeting Day.

Starting a Conservation Fund may not happen overnight, and it’s very normal to encounter setbacks. The Town of Huntington, for example, began laying the groundwork for a Conservation fund in the 1990s, only to have their proposal narrowly voted down at the 1999 town meeting. But advocates persevered in Huntington, and voters approved an article approving a Reserve Fund the next year, which has been used to fund projects ranging from renovation of a historic town hall to purchase of conservation easements, to trail restoration work. Twenty years later, as of 2018, the Conservation Fund has used $96,000 to secure an additional $576,000 of additional funding for local conservation projects, six times the amount the town paid out itself.

Warning Language

If a conservation fund will be voted on by the citizens, the warning language for the article should be simple and clear. Excess language may unnecessarily limit use of the fund. Several examples include:

- To see if the Town will vote to establish a Conservation Fund to conserve Weybridge land and waters for agricultural, forest, wildlife, recreational, or natural use;

- To see if the town (of Calais) will establish a reserve fund under 24 VSA 2804 for the purpose of acquiring real property or any rights or interests in real property, pursuant to 10 VSA Chapter 155;

- A reserved fund for conservation and related purposes such as land acquisition, open land preservation and other conservation activities that area consistent with the objectives of the conservation commission as outline by the State of Vermont and Hartford Town Plan.

Most towns give their funds names such as the East Montpelier Conservation Fund, the Williston Environmental Reserve Fund, and the Norwich Conservation Trust Fund (which was established in 1974 and is the oldest local conservation fund in the state). Choose a name that will have a broad appeal in your community and will not be perceived as too narrow or bent on a particular cause.

Use of Conservation Funds

Monies from a conservation fund can be used for various purposes, depending on the statute and the language used to establish the fund. If the fund is created under the statute chapter for conservation commissions, then the fund must be used “only for purposes of this chapter.” Most often, local conservation funds are used for the permanent protection of land, that is, to purchase land in fee simple ownership or acquisition of rights to land, such as conservation easements. A conservation fund can be used to purchase rights of first refusal, options to purchase, long-term leases, and land through a bargain sale.

Journey’s End in Johnson: Journey’s End is a well-used swimming hole and spectacular waterfall carved in the bedrock of Foote Brook, a cold water stream which flows into the Lamoille River. The property contains 25 forested acres along Foote Brook. The brook contains high quality trout habitat and the property hosts deer yards, songbird habitat, and a forested buffer along Foote Brook. Access is a corridor from Plot Road. Read More

Funds are also used for technical assistance in land conservation projects, including legal work, surveying or mapping, appraisal or closing costs, easement stewardship costs. The East Montpelier Conservation Fund can be used for activities such as appraisals and surveys “with the understanding that such funds will be reimbursable [by the landowner] to the Fund if conservation is not achieved.” The local fund in Brattleboro was set up as a revolving loan fund to help protect agricultural lands in town. The Brattleboro Agricultural Land Protection Revolving Loan Fund can be used to purchase or assist in the purchase of interests in farmland that is threatened with development. The Williston Environmental Reserve Fund has one of the broadest purposes of any local conservation fund. One of its funding requests stated that the fund can be used “for the purpose of preserving open space, park lands, and natural resources lands by performing inventories, investigations, and surveys; negotiating options, purchase agreements, and other legal documents; and purchasing or otherwise acquiring lands or interest therein with any unexpended portions of such funds to be placed in a reserve fund to be used solely for the purposes in future years.” The Williston Reserve Fund has been used for land conservation projects several times since its formation in 1989. In a more atypical use, the fund was used to help a farmer build a manure pit to keep agricultural run-off from flowing into a nearby river. (The farmer had already donated an easement for a canoe access to the river.) As long as the farmer kept the land in agricultural production, the money was considered a grant; if he stopped farming, then the money would be considered a loan.

Funding of a Local Conservation Fund

Once you have support for the idea of a Conservation Fund, there are a variety of ways you can put money into it. In most Vermont municipalities with such funds, the monies are raised from town appropriations, most often requested annually. These town appropriations can be either a lump sum or a certain portion of the tax rate. For example, Hinesburg has raised its land conservation funds by requesting a lump sum of $5,000. The voters of Charlotte agreed to levy a tax via the following article: “Will the Town vote to authorize the selectboard to increase the tax rate by no more than two cents for a ten-year period to establish a conservation fund.” This raised approximately $70,000 per year for land conservation projects. This strategy is sometimes referred to as the “penny for conservation” tactic.

These requests for town appropriations are included in the town warning of the meeting at which the citizens will vote. In Shelburne, the town’s Natural Resources and Conservation Committee encouraged the town to increase its town appropriations by changing from an annual lump sum of $15,000 to one cent on the tax rate. The first year the one-cent rate generated approximately $58,000.

In many towns, the lump sum allocation to the local Conservation Fund is a line item in the town budget or is a budget item under the conservation commission. In addition to the town appropriations, other town revenues have been put into local conservation funds. For example, the Calais Conservation Commission arranged for a timber sale on one of the town forests. The timber harvest generated $16,500, which was put into the local Conservation Fund. Monies can also be raised by fundraising activities. The Norwich Conservation Commission sold ice cream and tee shirts and put the profit into its local fund. Several towns fund their local Conservation Funds through voluntary donations. It is important to note that donations to a town conservation fund are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service Code. For example, in 1999 the Hartland Conservation Commission sent an appeal letter to all town residents with the town tax bills; it received donations totaling $3,400 for the local Conservation Fund.

Warren’s Conservation Reserve Fund: Warren’s Conservation Reserve Fund was created to conserve forest lands through purchasing land and conservation easements. The Warren Conservation Commission is responsible for the fund and how money is spent. Each year a separate article is voted upon at Town Meeting to maintain the fund. Currently, the fund contains between 10 to 20 thousand dollars. Read More

Of course, local conservation funds can be funded through a combination of the methods discussed above. In Norwich, both fundraising activities and donations are used. Moreover, the neighborhoods in which the projects are taking place are encouraged to raise some of the money needed for the project.

The cost of conserving land varies by the land prices and development pressures in any given Vermont municipality. Some towns need to raise much larger funds than do others. Many towns with local Conservation Funds have realized that these funds can be designed to accumulate to significant amounts through relatively modest town budget contributions made year after year.

Administration of a Local Conservation Fund

The administration of local Conservation Funds also varies throughout Vermont. If the fund was created under the Reserve Fund statute, then the statute specifically states that the fund is under control and direction of the legislative branch of the municipality (24 VSA 2804). In many towns, the municipal conservation commission administers the local Conservation Fund with the approval of the selectboard. However, in East Montpelier, the East Montpelier Fund Advisory Committee was created. In Charlotte, an advisory committee is comprised of three people: the chair of the local land trust, the chair of the conservation commission, and the chair of the town recreation committee. Tasks for administering the fund include keeping financial records, developing policies and criteria to evaluate projects, creating an application process, and making recommendations on the use of the funds.

Conservation of Zack Woods: Zack Woods is a unique 393 acre area containing 9 undeveloped shoreline ponds, including Zack Woods Pond, Perch Pond, and a third of the shoreline of Mud Pond. Zack Woods Pond is one of the top 9 lakes in Vermont, ranked the highest for wilderness-like character. Zack Woods Pond has been a nesting location for the Common Loon since 1996, due to its unique natural island. The land is a popular destination for hiking, running, skiing, and snowshoeing. The ponds are a destination for swimming, paddling, and fishing. Read more

Maintaining Financial Records:

Bookkeeping and financial records are usually handled by the town clerk or the town treasurer. Funds are deposited in low-risk, liquid financial accounts, such as special savings accounts, certificate of deposit accounts, or money market accounts. For funds created under the conservation commission enabling legislation, the town’s trustee of public funds maintains the monies (24 V.S.A. 4505 [5]).

Developing Policies and Evaluation Criteria:

The municipal body that administers a local Conservation Fund must develop goals for use of the fund and criteria for reviewing any proposed expenditure from the Conservation Fund. The conservation commission often adopts such policies in consultation with the Selectboard. The following are often used to review projects for expenditure of local Conservation Fund funds:

- Projects that conform to the town plan or other town reports or land management plans;

- Projects that are adjacent to or near existing town land, other public land, or other conserved land;

- Projects that conserve agricultural lands;

- Projects that conserve productive forest lands;

- Projects that protect important water resources;

- Projects that protect or conserve lands that support significant ecological resources such as rare, threatened, or endangered plants or animals; exemplary natural communities; or important wildlife habitats;

- Projects with existing or potential educational use;

- Projects with historic or scenic value (or in or adjacent to an historic district or other area of importance to the town);

- Projects that provide recreational use or access.

A landowner’s willingness to place conservation restrictions on the land also may be taken into account when evaluating proposals. A primary requirement for use of the fund in East Montpelier is that the expenditure of funds must yield clear benefits to the town and must result from a voluntary agreement between the town and the landowners.

Other criteria can include financial considerations, such as projects that include a financially sound long-term management plan or include significant leverage of other funds. For example, Williston gives higher priority to proposals that maximize the reserve fund goals in a cost-effective manner. Preferred projects often are those that include partial funding from other sources, bargain sales, or donated easements, thus augmenting the Conservation Fund by leveraging other monies.

In evaluating projects, towns may also question the likely impact to the property and the town if the proposal is declined. Is the land at risk for development? Can the proposal be funded at a later date?

It can be very helpful to develop a map of conservation opportunities to aid in the evaluation of projects. Such a map can depict each of the values in the Conservation Fund’s purpose statement and show where those values overlap, hence offering more value to the town. Since an ecological conservation opportunity map would necessarily rank all parcels in town, but would only be used when a willing landowner comes forward with a proposal, careful messaging is needed to insure that residents don’t misunderstand its intention. South Burlington developed such a parcel prioritization in 2019 and 2020 to assist the South Burlington land Trust and others in ranking conservation possibilities.

Several towns have included in their policies a statement that each use of the fund is unique and thus the guidelines and list of evaluation criteria are general and are not exclusive. As the Barnard Conservation Commission wrote: “Experience with conservation projects teaches us that there are many creative and flexible ways to protect resources lands, and the Selectboard and conservation commission intend to take advantage of new opportunities as they arise.”

To assure that the town has the best choice of possible projects, the fund administrators should widely advertise the availability of the Conservation Fund. These funds are often described in a town’s annual report and on the town website.

Creating an Application Process:

Generally, the application process starts with interested landowners or potential project partners approaching the conservation commission or the Selectboard with their conservation plans. Sometimes the conservation commission will take the initiative and establish contact with a landowner. In Calais, a landowner contacts the conservation commission and requests to be placed on the agenda of the next regular commission meeting. At this meeting the conservation commission conducts a preliminary interview with the landowner to learn about the proposal and to explain the criteria that will be used for the evaluation. If the landowner chooses to proceed, a written application is submitted to the conservation commission.

Applications forms are generally short and simple to make the process easy for anyone to participate. Application forms are often available at the town clerk’s office or from the conservation commission or Selectboard. Application forms should be made accessible online as well. The information requested on the application form often includes the following:

- A description of the property;

- Identification of the significant resources to be conserved;

- Explanation of how the proposal is consistent with the criteria for use of the fund;

- Description of the public benefit to be derived from the project;

- Amount of money requested from the local Conservation Fund;

- Financial plan for the long-term management of the property.

Supplemental information that may be requested includes a project location map, photographs, deed restrictions, planning or zoning approvals, an appraisal, a project budget, draft easements, and a signed purchase and sale agreement.

In several towns, a short, preliminary application form is used to screen proposals. If the proposal is eligible for funding, the landowner fills out a longer application form. Technical assistance with project planning and application forms is available from many sources, including town officials, land trusts, local and regional planning commissions, and state agencies. As a demonstration of sincerity and personal commitment to the process, a landowner may be asked to share the cost of land appraisal with the town.

Recommending Use of the Conservation Fund:

The conservation commission or advisory committee must then review each application in accordance with the established criteria. This often happens at a regular interval or a specially warned public meeting. Additional information is requested as needed. A site visit may be an important part of the review process. In most towns, the fund advisory committee or the conservation commission then makes a written recommendation on the funding application to the Selectboard, who makes the final decision on any expenditure of the local Conservation Fund. In Hartford, the Selectboard holds a public hearing before making their decision. In Shelburne, the Selectboard can approve projects up to $15,000; projects costing more are voted on by citizens at a duly warned public meeting.

The administration of a Conservation Fund is stronger with a system of checks and balances such that the body that reviews projects does not have the power to decide how to spend the funds. In Barnard, if the conservation commission declines a project, the landowner can appeal to the Selectboard who can override the commission’s recommendation. Fund guidelines should state that no person having a direct interest in a project under review may participate in the decision. After a project is funded, a local group such as the conservation commission can assist with monitoring the property to ensure that any conservation easements or agreements are maintained.

In summary, a local Conservation Fund is an excellent way for a town to work in partnership with interested landowners, land trusts, and other organizations to undertake land conservation projects. It is a practical, cost-effective way to protect important conservation lands for present and future generations.

7-4 Grant Programs

As opposed to operating funds, most funding for conservation commissions projects comes from grants. The enabling legislation states that conservation commissions may “receive money, grants or private gifts from any source, for the purposes of this chapter.”

Commissions should not be intimidated if they have no or little grant writing experience, as they can tap into outside expertise and resources. There are many books and resources on grant writing. Libraries often have a separate section on grant writing sources and resources. Non-commissioners in town with grant writing experience may be able to assist. Workshops and courses are taught on fundraising and grant writing. Even professional grant writers and fundraisers can be hired for specific projects.

Grant writing takes practice and then improvements follow. Fortunately, many funders realize that volunteers are filling out many of the grant applications and thus make the applications as simple and straightforward as possible. If time permits, several commissioners should read the grant proposal and suggest improvements. Because most grants have specified open periods where they are receiving applications, keep a file with promising grant sources and their deadlines, and be sure to refer to it early as a project is conceived.

Conservation work can be paid for a variety of grant programs administered by an assortment of public agencies, non-profits, and private foundations. The world of grants is constantly evolving, with grant programs waxing and waning over time as funding priorities, politics, and financial streams evolve. However, some grants are relatively reliable sources of funding for conservation projects in Vermont, at least as of this manual’s update in 2021. See the VT Funding Directory Below are several of the more promising grant opportunities for municipal conservation.

Forest Legacy Program (FLP)

Administered By: Vermont Department of Forests, Parks & Recreation

Description: The FLP provides funding to conserve important forestland properties to protect them from conversion to non-forest uses. Landowners may sell property as fee simple title, or only a part of the property rights, while retaining ownership of the land.

Grant Details & Match Requirement: Provides for up to 75 percent of the costs of a conservation easement or fee-simple acquisition, including the costs of appraisals, surveys, closing costs, title work and insurance, and other associated costs. The remaining 25 percent must be matched by either the landowner or an assisting entity, such as a non-profit organization or non-federal governmental entity.

Example Projects:

- Lemington, Monadnock Mountain: Forest Legacy grant helped Town acquire the fee interest in a 1400-acre parcel, on which FPR holds an easement.

- West Fairlee, . Brushwood Community Forest: Forest Legacy Grant helped Town of West Fairlee acquire approximately 1,000 acres, on which FPR holds an easement.

Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF)

Administered By: Vermont Department of Forests, Parks & Recreation

Description: Used to create parks and open spaces, protect wilderness, and forest, and provide outdoor recreation opportunities. Project must meet an identified need from the Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP).

Grant Details/Match Requirement: Up to 50% matching assistance to state and local governments.

Example Projects:

- Bolton, 2003. Preston Pond Acquisition. LWCF Contribution of $31,457.00 towards acquisition costs.

- Williston, 2019. Catamount Community Forest.

US Forest Service Community Forest Program

Administered By: Vermont Department of Forest, Parks & Recreation

Description: The Community Forest Program provides financial assistance to tribal entities, local governments, and conservation non-profit organizations to acquire and establish community forests that provide community benefits such as: economic benefits through active forest management, clean water, wildlife habitat, educational opportunities, and public access for recreation.

Grant Details/Match Requirement:

Example Projects:

- Huntington, 2020. Huntington Town Forest: Received $385,000 towards acquisition costs for new town forest adjacent to elementary school.

- Montpelier, 2021. Hubbard Park Expansion: Received $258,000 towards acquisition costs for expansion of existing park.

Vermont Housing & Conservation Board (VHCB)

Administered By: Vermont Housing and Conservation Board (VHCB)

Description: Working with a statewide network of partners, VHCB funds the conservation of agricultural land, natural areas, forestland, recreational land, and the preservation and restoration of historic properties.

Grant Details & Match Requirement: VHCB requires a local match of 33% (using cash, in-kind services, or donated easement or land value) for funding local land conservation projects. Applicants are required to demonstrate municipal support from the town.

Example Projects:

- Middlesex, 2009: $271,000 VHCB Award towards acquisition costs for the Middlesex Town Forest, approximately 83% of acquisition cost.

- Huntington, 2020: $125,000 VHCB Award towards acquisition costs for the Huntington Town Forest, approximately 12.5% of acquisition cost.

Watershed Grants

Administered By: Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department; Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation

Description: for water-related projects that protect or restore fish and wildlife habitats; protect or restore water quality, and shorelines; Reduce phosphorus loading and/or sedimentation; enhance recreational use and enjoyment; identify and protect historic and cultural resources; educate people about watershed resources; monitor fish and wildlife populations and/or water quality.

Grant Details & Match Requirement: $3,500-$10,000, depending on project type.

Example Projects:

- Charleston, 2018: $2,000 for Echo Lake Ecosystem School Education and Milfoil Prevention Project;

- Charlotte, 2004: $3,200 for Natural Community Mapping & Assessment of Thorp and Kimball Brooks.

AVCC Tiny Grant

Administered By: Association of Vermont Conservation Commissions

Description: Seed money or matching funds to conservation commissions for specific land conservation, education and outreach, stewardship and management, and planning activities.

Grant Details & Match Requirement: $250-$600

Example Projects:

- Fayston, 2020: $300 for an ecological assessment of the Boyce Hill Town Forest.

- Brattleboro, 2020: $480 for installation of 20 interpretive signs along a trail loop.

- Enosburg, 2020: $350 to document wildlife activity with trail cameras on its conserved lands.

- Hartford, 2020: $250 to eradicate invasives species and promote growth of rare plant species on town-owned conserved lands.

- Putney, 2020: $600 to map occurrences of the invasive Emerald Ash Borer along town roads.

Recreational Trails Program (RTP)

Administered By: Vermont Department of Forest, Parks & Recreation

Description: The RTP is a program of the US Department of Transportation’s Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) that provides funds to states to develop and maintain recreational trails and trail-related facilities for motorized and non-motorized trail users.

Grant Details & Match Requirement: Provides up to $50,000 cap in grant funds with a 20% required match

Example Projects:

- Newport Center, 2017: $50,000 for Town Forest Trail Project, which included development of ATV and multiple use trail (4,500 feet long) within town forest.

- Chittenden, 2017: $15,718 for Downtown to School Trail Linkage, including new trail, trail improvements, and an 80-foot universally accessible trail.

- Northfield, 2016: $11,000 for Paine Mountain Town Forest Trail Restoration, including new puncheon bridging, a wooden footbridge, and other improvements.

Vermont Urban & Community Forestry Program

Administered By: Vermont Urban and Community Forestry Program, Department of Forests, Parks & Recreation.

Description: Annual financial assistance opportunities vary in size and scope. Most years, tree planting and community tree stewardship efforts are funded through the Caring for Canopy grant program. See the program’s website for current funding opportunities:

Grant Details & Match Requirement: Specific funding opportunities vary from year to year.

Small Grants for Smart Growth

Administered By: Vermont Natural Resources Council

Description: Provides seed money for community-based initiatives related to smart growth.

Grant Details & Match Requirement: Up to $3,000

Example Projects:

- Canaan, 2020: $1,200 to Canaan Naturally Connected to collect public input about usage of the Canaan Community Forest. Included determining how to enhance connectivity between the forest and nearby towns.

- Hyde Park, 2018: $1,500 to complete a guide that helps property owners navigate the local permit process when seeking the permits required to develop their land.

Municipal Planning Grant (MPG)

Administered By: VT Agency of Commerce and Community Development (ACCD)’s Department of Housing & Community Development (DHCD)

Description: The MPG encourages and supports planning and revitalization for Vermont municipalities to carry out statewide planning goals.

Grant Details & Match Requirement: Maximum of $22,000 for individual municipality; $35,000 maximum for a group of applications. Minimum cash match of 10%. Eligible communities compete with other applications from towns within their Regional Planning Commission service area.

Example Projects:

- Johnson, 2016: $14,000 for a town-wide Natural Resources Inventory;

- Fairlee, 2021: $8,190 for work on Conservation Subdivisions and Forest Block Bylaw Provisions.

7-5 Other Funding Sources

Beyond grants, conservation commissions can seek out support from other sources. Many people, organizations, and businesses are willing to support good causes by donating money, materials, time, or other talents. These types of donations are referred to as “in-kind services,” and can range from volunteer labor to donated materials to donated professional services (such as legal advice). Keep track of the value of in-kind services that are offered to your conservation commission, as you may be able to use the value of those goods and services to count towards other opportunities, such as for a match requirement for a grant.

For every project, Commissions should make a list of required goods or services and then discuss whether those items could be acquired through donations. Again, the mantra is “if you don’t ask, you won’t get it.” So don’t be hesitant to ask for donations. Examples of donated goods are food for Green Up Day volunteers or trees from a local plant nursery. Donated services can be printing services to produce an educational brochure for town residents or photography services to document a town event.

Conservation commissions often undertake a fundraising drive or event to raise funds for specific projects. Commissions must realize that sometimes fundraising events take more time and effort than they are worth. Also, a fundraiser should be in alignment with the conservation values of the commission or the project. For example, if a commission is raising money for a pedestrian path, then a car wash is not in keeping with the idea of decreasing vehicular traffic. A good example of alignment is the commission that sells trees and shrubs to town residents and uses the profit to pay for the town’s street tree program.

Listed below are several examples of fundraising events:

- The Joes Pond Association in West Danville has an annual contest and fundraiser to predict the date and time of spring ice-out on the pond. Tickets are sold for $1, and the winner splits the pot with the Pond Association which uses its share of the proceeds for water quality work and a fireworks display.

- Tree and shrub sale.

- Walkathon or Birdathon.

Don’t be afraid to get creative and have fun with the process! Because your cause is worthwhile take comfort in knowing that it is okay to ask for financial support.

APPENDIX A: SAMPLE RULES FOR MUNICIPAL CONSERVATION COMMISSIONS IN VERMONT

RULES

THETFORD CONSERVATION COMMISSION

I. AUTHORIZATION

The Thetford Conservation Commission (the Commission) shall be governed by all applicable state statutes, local laws and these rules. Conservation commissions are authorized in 24 V.S.A., Chapter 118, and Sections 4501 to 4506.

II. PURPOSES

The purposes of the Commission are:

a) to develop and maintain an inventory and conduct studies of the Municipality’s natural, scenic and recreational resources and other lands which have historic, educational, scientific, architectural, or archeological values in which the public has an interest (subsequently referred to as social resources) and to assist in planning for their conservation for the continuing benefit of the townspeople;

b) to recommend to the legislative body the acquisition of property interests to protect and conserve the Municipality’s natural and social resources and with the consent of the legislative body to accept gifts of land for conservation purposes;

c) to protect all water and wetland resources;

d) to foster the protection of sensitive natural areas and species;

e) to increase awareness of conservation and recreational goals in overall land use planning and zoning;

f) to allow for recreational uses on acquired lands which are consistent with conservation goals and have a minimum impact on the land;

g) to conduct a broad education program on issues which have an impact on local natural and social resources;

h) to make recommendations to and cooperate and communicate with municipal officials, commissions, groups, and organizations having similar concerns and with appropriate agencies of the regional, state, and Federal governments.

III. MEMBERSHIP

a) The Commission shall consist of a minimum of 7 and maximum of 9 members, appointed by the legislative body. Each member shall be a resident of the Municipality. The term of each member shall be for four years, except for those first appointed, whose terms shall be varied in length so that in the future the number whose terms expire in each successive year shall be minimized.

b) An appointment shall be for a four-year term, except for an appointment filling a vacancy shall be for the remainder of the term.

c) The legislative body may remove any member if just cause is stated to the member in writing and after a public hearing on the matter, if that member requests one. Just cause shall include unexcused absences from 25% the Commission meetings during the preceding twelve-month period.

d) All vacancies shall be filled by the legislative body forthwith.

e) All members shall serve without compensation, but may be reimbursed by the Municipality for necessary and reasonable expenses incurred in the course of their duties.

IV. PROCEDURES

The Conservation Commission generally functions as an advisory body to various municipal bodies, reporting ultimately to the legislative body. The conservation commission Chair shall develop an agenda for each meeting. Clear lines of communication are important to the proper function of the Commission, its committees, and other municipal bodies. In general, projects and decision-making are to proceed along the following guidelines:

a) The Conservation Commission will develop its work program and assign specific tasks to its committees. The committees may present suggestions for projects.

b) The committees will develop recommendations for Conservation Commission approval and/or amendment.

c) The Conservation Commission will present approved recommendations and/or plans to the legislative body.

d) Final decisions and actions are the responsibility of the legislative body.

e) The Commission and all of its committees shall operate in accordance with the Vermont Open Meeting Law.

V. OFFICERS

1) The Commission shall elect the following officers at the annual meeting (see section VI) of the group:

a. A Chair, who shall preside at all meetings of the Commission at which (s)he is present, and shall direct the work of the Commission. (S)he shall submit a brief annual report to the legislative body and, upon their adoption to the annual Town Meeting, which report shall review the Commission activities for the year past and present the Commission plans and prospects for the coming year.

b. A Clerk, who shall keep minutes of all meetings and proceedings of the Commission and record any action taken by the Commission. (S)he shall post public notices of Commission meetings and give notice to individual Commission members when necessary.

c. A Treasurer, who shall recommend action on all bills received by the Commissions. Payment for all invoices greater than $200 must be authorized by a majority vote of the Commission. The Treasurer shall prepare and present a financial report at each meeting of the

Commission, and shall submit an annual financial statement, approved by the Commission, to the Municipality.

2) The Commission may also elect other officers it deems appropriate including Vice-Chair, who shall assume all duties and powers of the Chair in his/her absence or when the Chair so requests.

3) All officers shall be elected for a one-year term and may be reelected for successive terms in the same office.

VI. MEETINGS

a) Commission meetings shall be open to the public, and be held at 7:15pm on the 2nd and 4th Wednesdays of each month unless otherwise advised. Special and emergency meetings may be held at other times in accordance with the Vermont Open Meeting Law. The Annual meeting will be the first meeting in May.

b) All records and minutes of any Commission meeting or action shall be filed with the Town Clerk and be available to the public.

c) A quorum shall consist of the presence of a majority of the members. No action shall be taken without the affirmative vote of a majority of those voting. Any member unable to attend shall notify the Commission in advance of the meeting date.

d) In order to secure and preserve the highest level of public trust in the deliberations and decisions of the Commission, it is incumbent upon each member not only to scrupulously avoid any act which constitutes a conflict of interest established in law but also to avoid any act that gives the appearance of an undue special privilege or a conflict of interest. A member shall withdraw from all participation, in any matter including all formal and informal discussion and voting, in which the member concludes that (s)he may have a conflict of interest or upon the assertion that there is a reasonable public perception that a conflict or a special privilege may exist.

VII. PRINCIPLE FUNCTIONS

Within approved budget guidelines, or as otherwise authorized by the legislative body, the Commission may engage or retain the services of any person, partnership, company or corporation necessary to provide specialized assistance required to support the functions of the Commission. The principle functions of the Commission shall be:

a) Inventories – The Commission may prepare and maintain an inventory of the natural resources of the Municipality. This natural resources inventory may include but not be limited to the following: prime agricultural and forest lands; soil capabilities; water resources; floodplains; known mineral resources; unique or fragile biological resources; scenic and recreational resources; and other open lands. The Commission shall also be responsible for the preparation and maintenance of an inventory of the land-related social resources of the Municipality. This inventory shall include but not be limited to those resources which possess natural, historic, educational, scenic, cultural, scientific, architectural, or archeological values to the public. These inventories shall

be available for use by the Municipal government and the public for continuing reference in all matters which may pertain to the conservation of the natural and social resources of the Municipality, including amendments or revisions to the Town Plan, zoning ordinances, subdivision regulations, highway plan, and to any applications made there under.

b) Land Acquisition – The Commission may, on the basis of the inventories or other appropriate study, recommend to the legislative body the purchase of, or the receipt of as a gift, specific land and/or property rights (including easements) or other property for the purposes set forth in Article II. The Commission may solicit or suggest sales or donations of specific interests from landowners. Subject properties and/or rights may be acquired by the Municipality, or may be acquired by other suitable organizations, for example, land trusts. Properties and/or rights acquired by the Municipality shall be by consent of the legislative body or affirmative majority vote of the Municipality. Each recommendation by the Commission may include an estimate of the acquisition-related costs to the Municipality. Each recommendation by the Commission may include an estimate of the acquisition-related costs to the Municipality, including but not limited to legal counseling, surveying, appraisal, effect on the tax base and the tax rate, and the proposed source of funds to be used for acquisition and related costs.

c) Land Management – The Commission shall exercise stewardship

responsibility for properties and/or rights acquired by the Municipality for conservation purposes. The Commission will propose plans and regulations for the development and use of acquired property interests which are consistent with the protection and preservation purposes for which they were acquired.

d) Public Representation – To the extent permitted by law, the Commission may represent the public interest in any matter which it determines may have a significant impact on the natural or social resources of the Municipality. The Commission may initiate recommendations to amend or revise Town Plans, ordinances, subdivision regulations, road plans, etc. for consideration by the appropriate authority. The Commission shall make recommendations to any municipal, regional, state or federal body which it feels are needed to implement the purposes of the Commission.

e) Education and Information – The Commission shall be responsible for the conduct of educational activities pertaining to local natural and social resources. It shall make information available to the public regarding these resources, especially those relating to public lands.

VIII. COMMITTEES

a) The Commission may function with both standing and ad hoc committees. Standing committees shall be established by a majority vote of the Commission; ad hoc committees may be established by decision of the Commission Chair. The Commission Chair shall appoint Chairs for all committees.

b) All committees shall function in an advisory capacity to the Commission. No action shall be taken by any committee without the prior consent of the Commission.

c) Committee membership shall be open to the public. Committee meetings shall be open to the public. The time and place of each meeting shall be posted. Minutes of committee meetings will be submitted to the Commission as soon as possible and incorporated with the records of the Commission.

IX. ADMINISTRATION

The Commission shall have the authority to request appropriations from the Municipality for its land acquisition, land management, inventory, education, information, and operating expenses.

Any other funds appropriated or donated to the Commission shall be carried in a public trust fund. This fund shall be under the trust and management of the Treasurer of the Municipality. This fund shall accrue from year to year for the use of the Commission solely for the purposes set out in Article II of these Rules. The Commission shall have the authority to receive gifts, grants or money from any sources for these purposes. Any funds from private, state, or federal sources which impose any obligation on the Municipality shall be accepted only by consent of the legislative body.

X. AMENDMENTS

These Rules may be amended at any regular or special meeting of the Commission by a two-thirds vote of the Commission. Written notice of intent to amend must be publicly posted, sent to each member of the Commission and the Chair of the legislative body at least seven days prior to the meeting at which the proposed action is to be taken.

XI. DISSOLUTION

The duration of the Thetford Conservation Commission is intended to be perpetual. In the event that dissolution is necessary, all existing public trust funds of the Commission remaining after payment of appropriate expenses shall be distributed to tax-exempt organizations emphasizing the same purposes as the Commission. Remaining funds originating from Municipality appropriations revert back to the Municipality’s general fund.

Adopted: September 12, 2007.